We are failing to see the encompassing beauty of old people

The lens acts as armor, hiding our worries, yet it also gives us strength, protecting us from our own anxieties of aging

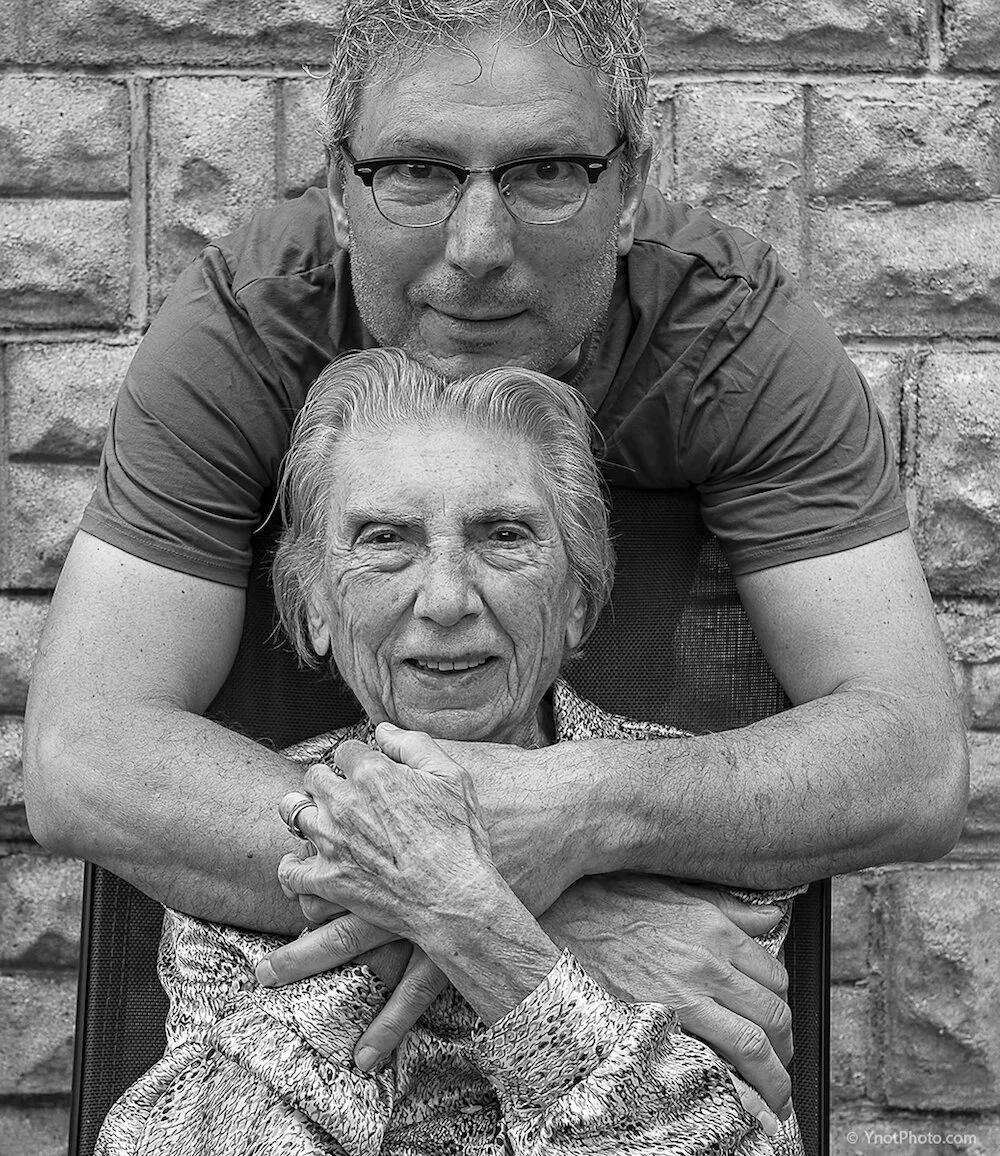

Tony Luciani, visual artist with his mother Elia who turned into his muse in their photographic journey

When I think about Tony Luciani, a poem by Emily Dickinson comes to mind, the one in which she describes what it takes to make a prairie: a clover, one bee and revery (To Make a Prairie, 1755). In the case of Tony’s story, it takes a son, a mother and a camera to make the most extraordinary journey in our perception of aging and frailty.

One step back. Tony is a Canadian visual artist. When his mother Elia turned 91 and it became apparent that she was beginning to be unable to look after herself, he invited her to move into his “home atelier.” What began as a matter-of-fact decision turned into a five-year-long artistic collaboration. Everything started when Tony was testing his new camera on a stand in front of the bathroom mirror and his mother peeked in. It was a moment of reflection and self-reflection.

Elia, an immigrant from Italy, was much more than a go-to model. While dementia was claiming part of her self, she transformed into her son’s muse. It was Tony’s artistic sensibility that “cooked” all the ingredients together: the frustration of sharing the same space with the serenity of everyday life, the evanescence of time with their playful attitude, the memories of the past, and the awareness of one’s own finitude.

There must have been moments of laughter as well as time for silent introspection. But as Tony said in his TEDTalk, he wanted to make sure that their domestic partnership turned into “a very long good-bye.” For those who didn’t have the opportunity to experience these moments first hand, there’s a moving collection of images. A gallery that invites us to question what we feel about aging and most of all - as Tony explains in the course of our exchange - why we feel the way we do.

Your mum photo-bombed you while you were testing your new camera. In a similar situation, another person might have asked her to keep clear. What made you make a different decision?

As an artist, and person who observes and thinks a bit differently from others, every moment for me, including life itself, is a blank canvas. I subconsciously and intuitively construct what I see and feel into potential works of art.

When my mother photo-bombed me, interrupting my self-indulgent camera lessons, I knew right away this was ‘the moment’ to hold on to, and it excited me. A spontaneous connection was made through creativity. That’s what I do: create. Including her in my art seemed like the perfect scenario. I got the most willing model, and in return, it gave my mother a taste of being valued again.

One moment she’s waiting to die, and in the next, she wants to live to tell her stories. She was feeling happy and wanted again. She deserved that. We absolutely needed each other for this collaboration to work, so the decision was very easy to make.

We encounter old people and we don’t see them. We don’t know what they think. If they live with us, maybe we don’t even ask them what they think. We need the lens of a camera to see them, to connect with them. How do you explain the fact that we have to take a step back to get closer?

If the need is to get away to get closer, then it’s perhaps the fear of delving into our own inner feelings and thoughts that pushes us along. The concern may be of attachment versus the disconnect with any physical avoidance. A camera only creates the illusion of a somewhat safer barrier between the two. The zooming in and focusing remain nonetheless.

We will be them, and that emotion of invisibility with older people makes us look away even more. If a camera initiates direction, then at least we can face our fears, instead of turning our backs to them. The lens acts as armor, hiding our worries, yet it also gives us strength, protecting us from our own anxieties of aging.

Do you think that our culturally-induced obsession for youth prevents aging and older people to appear in the media and this, in turn, promotes our inability to see them?

Indeed. We are a culture of promise and future, new and updated. We tend to dispose of the old, the slow, the used. Older people are hints of our own mortality. We don’t want to be reminded or see that, do we? Instead, bring on the young, fresh, and touched-up. Our society has turned away from the learned, experienced, and from the inner self, to plasticity and photo enhancements. Thus we see the outside, and not the within. Media is focused on the pretentious physical, and not on the beautiful realness found inside. Saying that, the beauty of old people is all encompassing, but we tend to mostly only see the wrinkled faces of our future selves.

We are used to pictures that highlight the flawlessness of women’s skin, but your close-ups of your mum’s wrinkles are so fascinating. As an artist, what do you make of this duality in the representation/perception of the female body?

The stories are found within those lines. They are about life and its experiences. As a painter who does portraits on occasion, I always ask the model to skip the make-up and hair gel. I want to see the underneath, to feel with paint what lies below the surface, and not mask it.

The analogy I often refer to are structures: buildings, that in the front are all about glamour and enticement, but around the back, they tell a different story. That’s where you’ll find the essence and guts of the building’s past. Fire escapes, waste bins, graffiti, give you a glimpse of what is behind the facade, and its glitz.

We all have something to hide and to conceal, but to know the truth, we must peel back to present it. The inside ‘is’ the story. Certainly, older people have more lifelines than most. Those wrinkles are earned. Acknowledging this, can only give pause to the narration they tell. Perhaps, for that reason alone, we should listen.

What is the most meaningful image you took of your mum? Why do you consider it meaningful?

This is a difficult one to answer, only because I, instead, mostly think of the process instead of the end result. But, if one had to be selected from the series, I keep coming back to the very first one. The unexpected happened. The ‘ah-ha’ moment which set everything up to what the series has become. When my mother unknowingly photo-bombed me, it was the impetus I needed to connect with her. I wasn’t looking for it, but it began a dialogue that turned into conversation, then morphed into a five-year-long project of collaboration.

The love of connection between us came from that single accidental impish peek around the blocked bathroom door. That was the all-important first sentence in our book of visual storytelling. The ideas just flowed after that.

You described your artistic journey with your mum as a “voyage of discovery.” What are the most unexpected things you discovered?

The biggest ‘unexpected discovery’ was of Mom regularly recounting the years that she didn’t have. I mean to say, she was married off at thirteen-years-old, and became a mother herself at sixteen. A normal teen life was lost. She went from child to adult and was stripped out of an average adolescence.

A lot of her stories revolved around her missed years. She wanted to play, go to school, date, and be with her friends, but responsibilities called. Mother, wife, and housekeeping chores took over. Her childhood dreams were shaken.

Another discovery was her edgy humour. The amount of time we spent while doing this series was reserved for outright laughing. It was a revelation to me. I always saw her as a ‘mother’ who provided and nurtured, and not necessarily one who loved to joke and play. Yet, during our collaboration on this project, her laughter was totally infectious. She went to bed most nights with a smile, and was excited to wake up the next morning for more. That, to me, meant everything.

What are the main differences you noticed between what you learned about aging and frailty through the creative process and our social/cultural “reading” of these events?

The most noticeable difference was of time lost. We look at older people as having a long life lived, and that is true, but time stands still for no one, and the moments of misplaced energy add up to an incredible amount. While we’re young, we think ahead and see a lasting, endless future, but when we get to “that age,” we look back and wonder how fast time has passed us by.

The Italian actress Anna Magnani once said: “Please do not retouch my wrinkles. It took me so long to earn them.” Do you think we need a different narrative of aging?

Of course. We need to accept that one day we will be that older person. Once we’re there, the hope is that we can cope with life without major intervention. To respect now is to be respected later. If we see the value of our older people, we hopefully will be valued once we take their place in society. We all wish for that.

One last question: when we think about the gifts of aging, we end up with a one-word list: wisdom. Based on your experience, what would you add?

‘Promise.’ The promise of fulfillment. It’s a true gift of aging.