Crack the code of aging

I have fears like everyone else. However, I think I fear running away from my fears more than continuing toward them and overcoming them

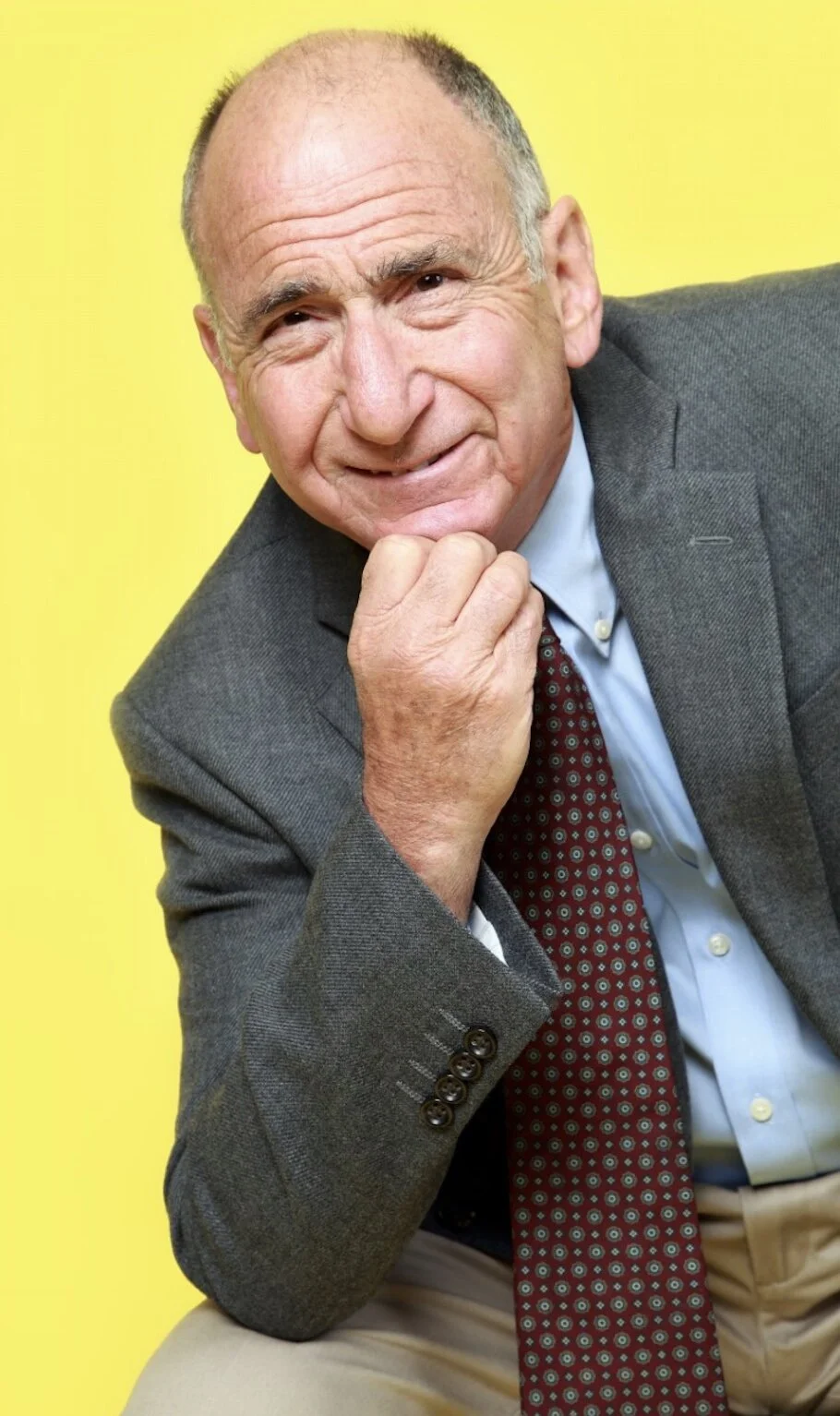

David Kleinberg, Vietnam veteran, journalist, entrepreneur, solo theater writer, and performer

When my years were inversely related to my sense of responsibility, I caught a flight to Cairo, in Egypt. Doing quality control for a national airline was an unpaid but priceless gig. Every month, in my pocket there was a ticket for an exotic destination and November seemed just the perfect time to pop to Africa. Carrying my tiny blue suitcase, I walked down to the local train station, with its modern bright red and green façade, to catch my train to the airport on a sunny and unexpectedly dry morning. Upon entering its tunnel-like entrance, in a contrasting game of lights, I saw the shadows of commuters going to the city for a day of work, while I was fleeing in the opposite direction to a new adventure. It didn’t occur to me that there was a false note in my journey until I arrived at the airport in Cairo. Waiting in line with my passport in hand, I realized that being alone in Egypt was not that great of an idea after all. But before I could dwell on my self-imposed misery, beginner’s luck took the form of a Canadian tourist with whom I started to talk at passport control. We agreed to visit the city together.

With my human laissez-passer, I dove into the most mesmerizing city. Cairo has the power to impact on all the senses at once. In the cacophony of a river of honking cars, the dust rising from the road mixed with the smell of grilled meats. Live chickens in wooden cages, with their head tilted on a side, eyed the pavement where black-clad women silently walked by. A bread vendor laid his bread on a sheet of plastic on the pavement at an intersection. A gaunt dead white horse rested in a ditch while the muezzin’s voice rained from the sky. The movement was endless, without a center of gravity and I felt pushed along by an invisible current until I finally sat on a wooden stool in a dimly lit square in front of a metal plate full of local delicacies.

The following morning we woke up very early. We drank black coffee and caught a white cab. From the lowered windows, we saw the city and its uninspiring gray apartment blocks slipping by. The taxi driver took us to a stable as we requested. Actually, it was just a concrete construction with a rusty metal door. In the half-light of the interior, we saw countless horses of every color, shape and size. We turned down the offer of a white Arabian horse that looked ready to ride on the wings of the wind and we ended up with two good-natured brown horses with pointed muzzles like seahorses, all too happy to leave their cramped room. The powdery red sand of the desert rose rhythmically in rolling clouds around the horses’ hooves and in the distance I spotted the Sphinx and, partially hidden from view, the great pyramid. I had longed to be there for innumerable years and now I could touch the walls with the tips of my fingers, I could trace in mute awe the signs carved thousands of years before. In my memory, it felt like breathing a thousand breaths at once.

Fast forward thirty years, the image of the Sphinx and the great pyramid re-appeared in a flash while I listened to the voice of David Kleinberg. It was difficult for me to weave the pieces of his story together, to see the thin filigree of his life against the light, to unravel the riddle of his life. I was there, with a black and white clip of a Vietnam veteran calling out LBJ in a brief, moving statement. A man on a scene in San Francisco sharing the brutally honest story of his recovery from sex addiction. A loving husband for at least this moment taking care of his ill wife. What was the image on the pieces of his life’s puzzle? And then, all of a sudden, I saw it emerging from the fragments of his reflection and our conversation. I grinned silently within myself. Challenging himself along an unscripted road, David’s story is all about this: aging is nothing more than living.

Tell us a bit about yourself and your story

I was born in San Francisco in 1943, and, unlike your story, have never lived anywhere else but within this beautiful city. Both my parents were Jewish, but they were non-observant. I had two younger sisters and a younger brother. And although my father had seven siblings and my mother five, we had no family on the West Coast other than one of my father’s brothers. In essence, with all four of our grandparents also deceased, we pretty much grew up without much beyond our own family.

It seems that you started over many times. What does it take to do so?

So, from my perspective, I don’t believe that I ever started over at all. I believe that my life has led me pretty much along one continuous, connecting path, though, from a first glance, they might seem different. I think I was born with a sense of curiosity about the world, and a need to share that with others.

If I step back, I believe that describes all the paths that I have been sent to explore: print journalism, television journalism, teaching, stand-up comedy writing and solo theater writing and performing and, now in this new moment, taking care of my wife.

I read you were a reporter during the Vietnam War. What took you there?

I did not take myself there. I was taken there by the United States Army. In 1964, the United States had just taken its first steps to defeat communism in Vietnam. It was about that time I dropped out of college to travel in Europe and the Middle East. In doing so, I was aware I could be drafted, but arrogantly I figured that the powerful American military would quickly subdue the Viet Cong, and I could casually return to school and renew my deferment from the military.

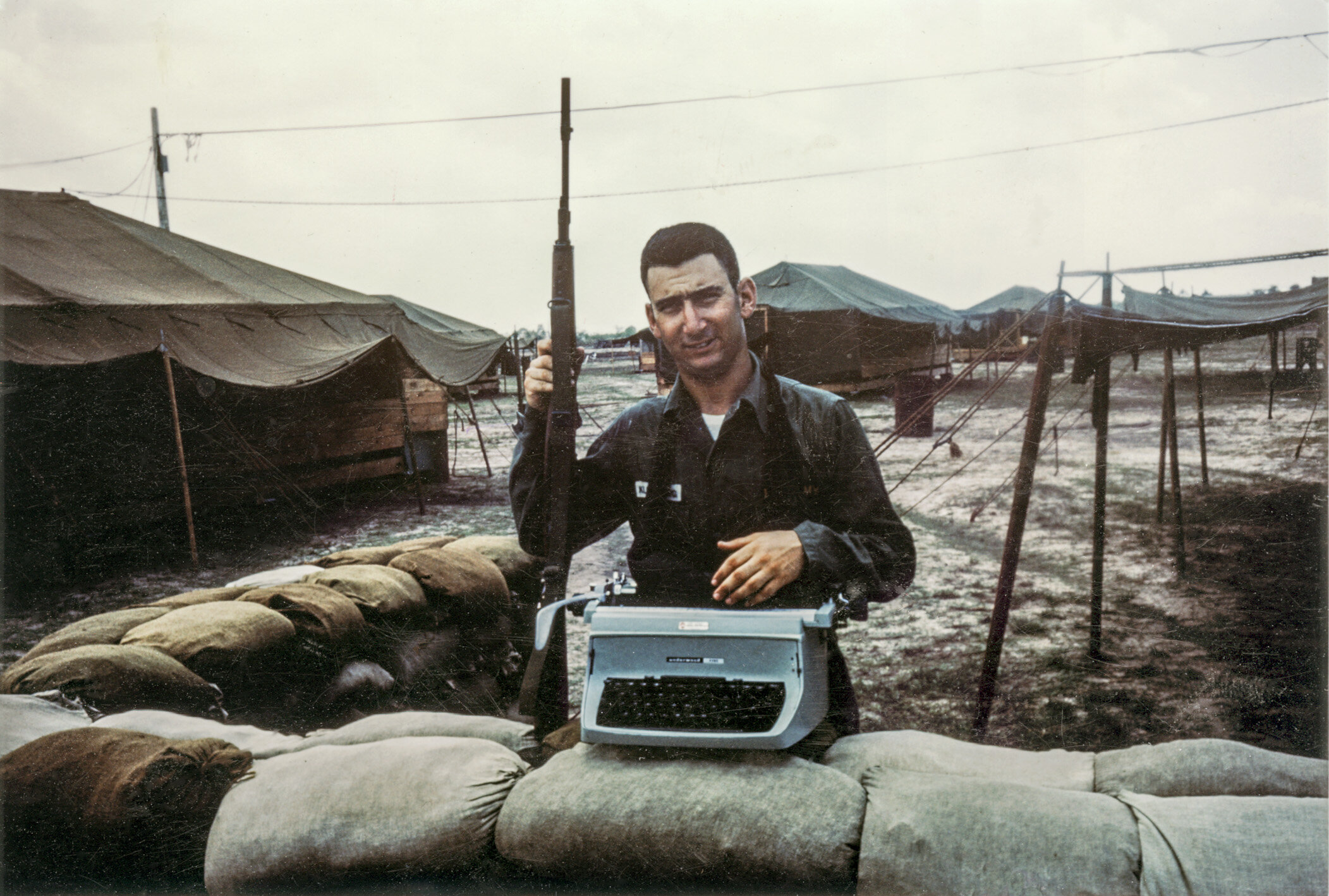

I was wrong. While traveling in Israel, I got drafted, and in March 1966, I arrived at Cu Chi, Vietnam as an information specialist with the 25th Infantry Division. I had by that time already had four years of newspaper experience at the San Francisco Chronicle, and the Army made one of those rare mistakes when they actually put the right person in the right place.

Vietnam was one of the most powerful experiences of my life. People will ask me, “What is war like?” My answer has always been: “War is like everything else in life – only much, much, much more intense.”

I had a blessed experience in Vietnam. I went out in the field with the soldiers and – while the battles were going on - just took pictures, came back and wrote stories for the division newspaper and magazine. After a few months of that, the Army sent me down to Saigon to be the editor of the division newspaper where I lived off base and worked in civilian clothes.

But I did experience tragedy at the very end of my tour. Nine days before going home, I still had five days saved of R&R (rest and recuperation), an army-created brief vacation from the war. I didn’t feel like being in the country if I didn’t have to, so I spent the time in Bangkok. While I was gone, the base camp was mortared, and a rocket directly hit the tent I lived in for a year – killing three of my buddies and wounding the six others. And so I came home to join the anti-war movement.

People have asked me if I had survivor’s guilt over this tragedy. I was angry, I was devastated. But, ultimately, I was glad I did not die. So I guess I can say that I have guilt over not having survivor’s guilt.

Fifty years after that attack you returned to Vietnam. How does aging help you to cope with a traumatic past?

My return to Vietnam turned out to be very cathartic. But I hadn’t had any interest in going back over all the time. And, truth be told, I believe I went back primarily to perform the play “Hey Hey LBJ!” in Vietnam so it would make good marketing material to perform it when I got home.

However, the moment I arrived in Saigon, the past overwhelmed me. I was up every night at 3 a.m. looking for the first flight home. But I was able to come to peace in the end when I went back to the alleyway in Saigon where I had lived 50 years before editing the division newspaper, just hoping to see if the building I had lived in then on the upper second floor was still there.

When I arrived at the spot, I found the building exactly as it was a half century before, and while I was standing there crying, looking up at the second floor (above where the Vietnamese family of nine that had lived below me with no more space than I had above them), a guy pulled up on his motorcycle, and started to enter the house.

I said to him, “Hi, my name is David Kleinberg. I’m from America.” And pointing to the second floor, I said, “I lived there 50 years ago.” And he said to me, “I lived here 50 years ago. I was 8 years old then. I remember you.”

And so after I visited with him, his wife and his two young kids, I went to the church next door where a service began. I was the only Jew in a congregation of Catholics, the only American in a congregation of Vietnamese, and the only person in the congregation who could not speak the language of service. But during the hour and a half service, I could understand the only word that counted, which was “Amen.” Which means: So be it.

Does the perspective on the events change, too? I mean, do you find a sort of bigger, deeper meaning?

Assuming you’re talking about losing my buddies, yes, the deeper meaning that I believe I discovered in reliving this part of my life in this theatrical work is that maybe God had spared me on that April 10, 1967 day so someday I might be able to tell that story of war and pain.

Where does your interest for entertainment come from?

Ironically, even though I was the editor of the Sunday entertainment magazine at the San Francisco Chronicle for 14 years from 1980 to 1994, entertainment has never been a natural core interest of mine. As a young person, I was always interested in sports. I grew up only a few blocks away from where the San Francisco 49ers played their games in a mammoth 60,000-seat stadium. It did not matter – given that I have no athletic ability – that I was the worst player in any sport - football, softball, and basketball, depending on the season - in the entire schoolyard. I took joy in the competition but more joy in the kids who I played with and competed against.

I think my interest in sports drew me toward journalism because if I could not play sports, maybe I could write about them. At 16, I started writing sports stories for a citywide neighborhood free publication. At age 19, while still in college, I became a part-time copy editor in the sports department at the Chronicle. When I returned from Vietnam at 24, I rejoined the sports department, but soon the paper assigned me to work in the various Sunday sections, as an editor and writer. One of those sections included the Sunday Datebook, at that time largely considered the entertainment Bible of the Bay Area.

And then, for some reason, in 1980, the paper decided to implant me as the editor of that publication, even though I didn’t know a damn thing or care much about entertainment. That job encompassed the last 14 years of my 34 years at the San Francisco Chronicle. In 1994, I had nowhere else to go at the paper. I already had the best job you could possibly have at the paper – I could go see anything in town at any time with the best seats. But the creative challenge of that job was gone. I felt I could take the publication no further.

What did you do next?

When I decided it was time to move on, I was given a business opportunity that arose with an organization called Elderhostel, a travel/education program for older adults. My wife Patrice was working as an independent consultant for them, helping assist the local organizer for programs at San Francisco State University.

We established our own nonprofit organization called Bay Area Classic Learning, and became a provider for the national organization, and soon became one of the largest providers in the country. Our job was to make contracts with various Bay Area hotels to provide food, conference space and lodging, hire hosts and teachers, and submit programs to the national organization, which provided registration and marketing.

How did you become a comedian?

I had loved comedy throughout my life. And during the 60s, when I was in my 20s, living in my native San Francisco, I would attend a comedy club called the “Hungry i” where I saw such comic legends as Lenny Bruce, Bill Cosby, Dick Gregory and Woody Allen. When I became editor of the Sunday Datebook, I decided to make sure comedy was given the coverage I felt it deserved.

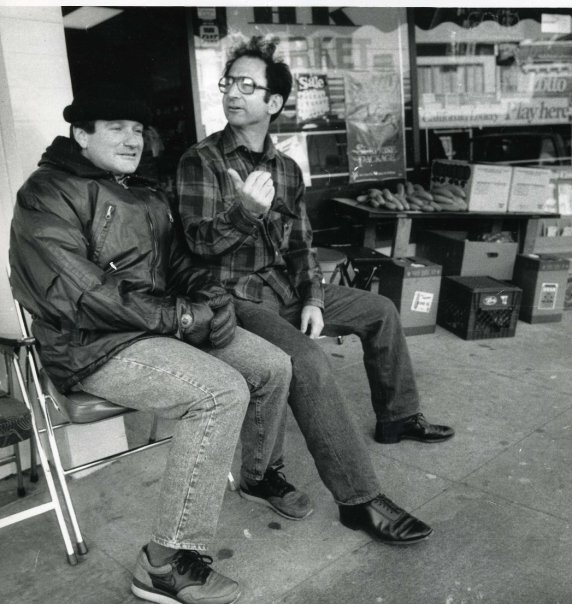

When I left the paper, though our BACL Elderhostel business was extremely successful, I felt a creative void, and I turned to comedy to try to fill it – starting with open mics, but building up to enough success that during the ten years I did comedy, I had the privilege to perform on the same bill with five of what Comedy Central labels the top 100 comedians of all time – Robin Williams, Sinbad, Dana Carvey, Richard Lewis and Bobby Slayton.

Is comedy a way for you to rewrite things, to apply a sort of filter to reality?

No, I don’t think comedy is a filter of reality. Like the things I’ve done in the past as a journalist, I believe the object of the comedian is to tell the truth. Comedians are truth-sayers. What makes people laugh is when you tell them the truth it allows them to figure it out in a way that gives them a release.

I love comedy so much I guess because I like the challenge. I have fears like everyone else. However, I think I fear more running away from my fears than continuing toward them and overcoming them.

And I loved comedy because it presents the greatest risk (i.e., fear) of all the arts. You have no ensemble to blend in with, no painting nor musical instrument to hide behind. You are out there all alone. That is why when a comedian succeeds, they say, he has “killed the audience.” And when a comedian fails, they say he has “died on stage.” That is, kill or be killed. There can be no greater risk.

You also wrote and performed a solo theater work on the hushed topic of sex addiction. It seems you have a knack for venturing into less traveled roads (and sharing your experience.) What is your take?

My take would be that the only way to grow, share and contribute to others in this life is to proceed through action, which involves risks. I certainly felt most tested in that regard by bringing my sex addition and recovery story (20+ years recovery now) public by writing and performing this story on stage. I decided the subject was incredibly important and needed to be shown to the world. Sex addiction is far more stigmatic than any other addiction there is. If you go and tell your boss I have a problem with alcohol but I’m going off to the 12 Steps or a recovery to deal with it, your boss will say, “I’ll drink to that.” But if you say you’re a sex addict, you’ll be looking for a new job.

The play is titled “The Voice: One Man’s Journey Into Sex Addiction and Recovery.” And there actually is a true scene in the piece where I perform part of the play for my wife who is absolutely outraged about the prospect of being known publicly as the wife of a sex addict; but as the play advances, it also shows her journey toward realizing how much the work could help others, and, without reluctance, eventually -- knowing that she has the final say as to whether I will perform the work or not -- brings her blessing to it.

When I was in my addiction, as it happens with all addictions, it was actually a way of not dealing with your pain. And the pain I had I believe started in my first marriage: my wife suffered from depression and I felt I had no control over our life. The addiction continued into my second marriage as a way to cope with the chaos that happened within the family as I married a woman with three boys and I had two daughters who were profoundly unhappy in that situation.

I read about your travel through Africa: how are these challenging experiences impacting on your aging?

That trip through Africa took place in 1968 – now 53 years ago. I don’t believe that those challenging experiences are apart from the continuing compendium of experiences that already had started in my life (a six-month tour of Europe and the Middle East in 1964) and since then as my life has moved ahead with challenging encounters.

I would say that actually the most impactful thing that has happened in my life, the most challenging experience, was one that had remained in my subconscious until I discovered it through a body therapy close to 40 years ago. It was the experience that my mother never picked me up when I was a baby (my mother and I actually shared that experience, given that her mother had died giving birth to her, and she too was never picked up as a baby.) On a subconscious level, I probably believed that I needed to do something special to be loved. For after all, if your mother couldn’t love you, if you cried and cried and no one picked you up (as I relived in the therapy), who could love you? Thus the drive to be someone.

Can you tell us something about your aging journey?

I feel honestly that I may be at the most creative part of my life, probably the most peaceful with who I am at this point, and physically okay. In fact, I am still unbelievably blessed to be able to play full-court basketball once a week – even though I’ve been the shittiest player on the court for more than 50 years. After more than two decades, I’m also still very involved with my 12-step recovery program, and believe that anything I have achieved and can achieve comes from a source outside myself and far greater than myself. I wrote a play about a dog - actually me befriending a neighbor’s dog and taking to jog - and I philosophize that we are the only creatures on earth that have a choice that comes with the challenge of having to perfect ourselves.

What’s next in your life?

I am blessed to be able to support the most beautiful and wonderful woman, my wife, in her current journey to restore her health.

Left: David as Army Combat Correspondent in Chu Chi, in Vietnam in 1966

Center: David and Robin Williams sitting out in front of a Chinese grocery store in San Francisco in 1987 after he interviewed him for "Good Morning, Vietnam"

Right: David playing at the Mission Playground basketball court in San Francisco a few weeks ago